The Episcopal Church in Delaware

Delaware Communion Magazine | Fall 2025

- 302.256.0374

- www.delaware.church

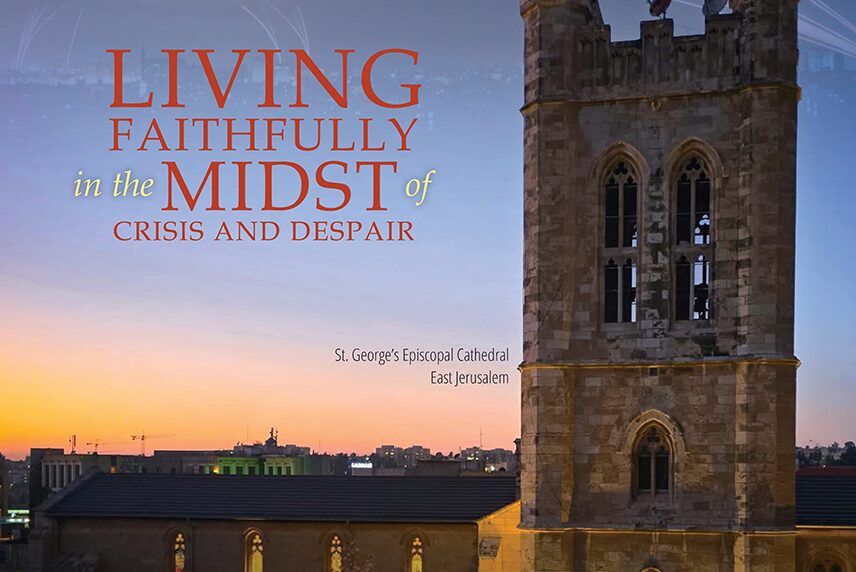

Living the Questions

in the Holy Wild

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

― Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

Photo: under license from Shutterstock

by the Rev. Canon Martha Kirkpatrick

What question am I living today? One of them surely is “in this crazy mess of a world, with so much need and suffering, what is my work to do?”

Photo: Martha Kirkpatrick

I’ve known for a while now — since long before I was a priest — that my work lies at the intersection of the natural world and my Christian faith. My faith informs me that everything is connected to everything else and held in God, and that humans suffer from a profound alienation and an illusion of separateness. To mend the breach between ourselves and the sacred wild, and begin to heal the planet, we need to foster a deeper connection with the more-than-human world, from a passive to an active connection, from “nature as scenery” to seeing the world as an intricate web in which we are radically interconnected. We are each responsible for our own evolving; no one can do it for us. The heart of that work is relationship.

Photo: Martha Kirkpatrick

In June, I traveled to Ghost Ranch in New Mexico to wrap up two years of work with the Center for Wild Spirituality. Forty-five of us were ordained either as Wild Guides (me) or as Eco-Spiritual Directors. We were ordained individually in the wild and by the wild, where we made our own vows, and then gathered together to make a wild covenant. The center of my vows was to be rooted in Christ consciousness. I also vowed to love all beings; to hold myself in singularity and in unity with all life, and to dedicate myself to companioning others to grow into deeper relationship with the holy wild and the Sacred.

There is much more to be said here, and I am more than happy to explore further with anyone who is interested. Suffice it to say that this is edge-walking, a re-imagining who we are and our place in the cosmos.

It has been a long journey from my many years as an environmental regulator. A lot of good came out of those decades, but they were mostly about law, science, and engineered solutions to reduce our impact and clean up our messes. Important, but nowhere near enough. We are at a different inflection point now, one that asks profound questions about who we are and our place on this earth. We need to engage not only our brains, but also our spirits, hearts, bodies, and imagination.

Robert Macfarlane, who has written much on nature, people, and place, has a new book entitled Is a River Alive? He writes, “How we answer this strange, confronting question (“is a river alive?”) matters deeply. Even asking this is a first step.”[i] He explores how rivers are becoming central to a profound reimagining process.

Robert Macfarlane, who has written much on nature, people, and place, has a new book entitled Is a River Alive? He writes, “How we answer this strange, confronting question (“is a river alive?”) matters deeply. Even asking this is a first step.”[i] He explores how rivers are becoming central to a profound reimagining process.

“Muscular, willful, worshipped and mistreated, rivers have long existed in the threshold space between geology and theology. They give us metaphors to live by, and they decline our attempts to parse them. Unruly, fluid and utterly other, rivers are — I have found — potent presences with which to imagine water differently.” [ii]

In the Episcopal Church in Delaware the opportunity to “imagine water differently” may be on the horizon. The Rt. Rev. Maryann Budde, bishop of the Diocese of Washington, has just recently invited us to be part of a process to establish a Mid-Atlantic Eco-Region, pursuant to Resolution B002: “Build Eco-Region Creation Networks for Crucial Impact,” which was passed at the most recent General Convention. An eco-region can be any region that is defined by ecological features, such as the Chesapeake Bay. The intention is to form eco-networks according to shared geographical boundaries and ecological concerns, which of course do not stay within political or diocesan boundaries. We would seek the endorsement/sponsorship of the presiding bishop’s office. Three regions have already been established and have received funding for organizational purposes according to resolution B002. The lead for the Diocese of Washington is the Rev. Pete Nunally, whom many of us know as he recently served as interim rector of St. David’s in Wilmington. This is an exciting opportunity, and I look forward to imagining what we might do together.

It will take breaking our long-established patterns of thought that objectify the world around us. “One way to stop seeking trees or rivers or hills only as ‘natural resource’ is to class them as fellow beings — kinfolk. I guess I’m trying to subjectify the universe, because look where objectifying has gotten us. To subjectify is not necessarily to co-opt, colonize, exploit. Rather it may involve a great reach outward of the mind and imagination.”[iii]

A great reach outward of imagination — “Ask the animals, and they will teach you;” it says in the Book of Job. “The birds of the air, and they will tell you; ask the plants of the earth, and they will teach you; and the fish of the sea will declare to you.” (Job 12:7–9). This takes daring to imagine that the world is animate and alive, and indeed, has something to teach us. For me, this is where I find hope, and where I feel God is calling us: to come home to our planet and find our place among our fellow beings.

[i] NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2025, 31,

[ii] Macfarlane, 30.

[iii] Ursula K. Le Guin, quoted in Macfarlane, 35.

The Rev. Canon Martha Kirkpatrick retired several years ago as canon to the ordinary for the Episcopal Church in Delaware, following her service as rector of St. Barnabas’ Church in Wilmington. Before her ordination, she spent two decades in environmental protection, including serving as commissioner of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection under Governor Angus King.