No Place to Call Home:

Voices from the Streets

and a Faithful Reponse

“How we choose to care for the most vulnerable among us says much about our community. …What if the good news includes breaking the cycle of poverty, and dismantling the systems that impoverish so many of our neighbors?” — the Rev. Patrick Burke

A two-part exploration by Cynde A. Bimbi and the Rev. Patrick Burke

on the human and systemic sides of homelessness in Wilmington, Delaware

Voices from the Street

by Cynde A. Bimbi

“I’m not ashamed — I’m homeless.”

Wilson has been living on the streets of Wilmington for nearly a year. “I got too comfortable in the beginning, during the summer months,” he admits. “And now — I’m cold.”

On this bitter, icy night, as freezing rain coats the pavement, Wilson huddles in layers not nearly warm enough. Luckily, he found refuge in a warming center in downtown Wilmington. He talks about his determination to find a way off the streets and carve out a path toward stability. Wilson also points out that unlike other cities that offer designated tent communities or provisions for the unhoused, such as, a pallet village in Georgetown, Delaware, here, the streets seem to be the primary refuge.

One evening, during a Code Purple — when temperatures in New Castle County drop below 20 degrees and emergency overnight shelters open — I had the chance to meet several people experiencing homelessness. Their stories were raw, deeply personal, and profoundly moving. I walked away not just with a new understanding of their struggles, but with a sense of connection. I felt like I had made new friends.

Wilson: “There’s no housing crisis — the city owns plenty of houses.”

Wilson doesn’t believe Wilmington has a housing shortage; he believes it has a housing priority problem. “The city owns plenty of houses,” he says. “They board them up and let them deteriorate, then they sell them to developers instead of making them affordable.” He’s seen countless programs that overlap, offering the same services, but not enough real solutions.

Wilson came to Delaware from North Carolina after his sister died. He said he entered a housing program but was forced out when he couldn’t pay two months’ rent upfront; St. Vincent de Paul offered to cover one month, but the program still insisted on two, which left him on the streets.

His struggles run deep. He suffers from bipolar disorder and PTSD, haunted by the memory of witnessing his wife and children die in a car accident — one he believes he should have been in. He explained that he sought help due to his medical condition and signed the required papers to release his medical records to a program in Delaware, but nothing ever came of it.

His first nights of homelessness were spent in a tent provided by St. Vincent de Paul. He eventually abandoned it to care for a young woman also living on the streets. Later, he’s back in a tent under an overpass — until authorities decided he was an “eyesore” and moved him. He points back to our earlier conversation, saying, “Here, it seems like there is no place to go.”

Still, Wilson is fighting for change. He recently applied for a job paying $18.50 an hour, but he knows the cost of a room will make it hard to save.

Our conversation ended with Wilson saying, “There are people out here that need help. We’re just like anyone else — I was raised right. Yes ma’am, no ma’am. But out here, you learn survival mode. And that can make you dangerous.”

Jeffrey: “It’s been a minute.”

When I ask Jeffrey how long he’s been homeless, he just shrugs. “It’s been a minute.” That “minute” has been two years.

He isn’t scared — at least, that’s what he tells me or maybe, himself. He picks a safe-looking spot to sleep, preferably somewhere with cameras nearby.

Jeffrey got out of prison and had nowhere to go. He came to Wilmington because his children live here, but without ID, money, or a support system, he was trapped. “You can’t get a job without an ID, and you can’t get an ID without money.” It costs $40 to get identification — an impossible amount when you have nothing. He discovered Friendship House, which helps unhoused individuals get an ID for $5, but scraping together even that much is a challenge. “I’ll save it up, but then the weekend comes, and I’m too hungry to wait for Monday.”

He watches landlords build high-dollar housing while abandoned homes sit empty, just out of reach.

Photo taken on March 4, one night after two consecutive nights of Code Purple.

Malcolm: Jump Rope and Hustle

Soft-spoken and gentle, Malcolm is an artist — a jump rope dancer. You might see him on Wilmington’s Riverfront, performing his rhythmic routines, hoping for a break. He shares his talent online, creating videos for YouTube and hoping that someone will notice.

But talent doesn’t guarantee a roof over your head. Like so many others, he keeps pushing forward, holding onto his craft as both a passion and a lifeline.

V: “You gotta do the work.”

At 62, V has seen a lot. He believes in hard work and that you get out what you put in. But even he is frustrated watching high-rises go up while abandoned homes stay empty.

I ask him if he prefers the term “unhoused” over “homeless.” His answer is simple: “No. Why? It means the same thing.”

He has noticed that more and more women — especially those with children — are experiencing homelessness. And when women and children are on the streets, men like him feel the weight of responsibility to protect them.

Kim: “Women can’t put up a wall like men can.”

Kim, 61, has been homeless for about a year. In her experience, homelessness affects women differently. “We’re nurturers,” she says. “And now, that part of us is gone.”

She spent time in Pittsburgh, later New Jersey, where she graduated from a university. She has worked in retail, landscaping, and gardening. She had a home and a beautiful garden that people admired. But when she opened her doors to some people she was trying to help, they took everything — all of her savings that was hidden in the house. Unable to recover financially, she lost her home.

Now, she doesn’t even have an ID. “I have an expired driver’s license, but nobody will accept it — even though my picture’s right there.” Without an ID, she can’t get a job.

Despite everything, Kim has a heart for others. “I hope I can say the right thing at the right time to help somebody.” She wants to set a good example for her children and grandchildren, scattered across the country, none of whom can afford to take her in. She refuses to be a burden.

Yet, among all the challenges she faces, one of the hardest is something most of us take for granted. “Finding a place to go to the bathroom.”

If she could send one message to the world? “Love one another. Do things for people — not for money, but to be kind.”

Samyra and her son, Conyers: Laughing to Keep From Crying

Samyra clutches her son, Conyers, as they take refuge from the cold during this Code Purple evening. He is one year old.

She’s been unhoused for a couple of months — some of the coldest months of the year. But she has a caseworker who is fighting for her. She goes to an online college, working toward a degree as a Medical Administrative Assistant, set to graduate in July.

She also has a nine-year-old son, living with her grandmother in New Jersey. Once she finds stable housing, she says they’ll be reunited.

“I laugh to keep from crying.”

Every night, she cries. “I’m afraid of losing my son,” she confesses. But during the day, she forces herself to smile. “I laugh to keep from crying. I don’t want him to see me cry.”

She believes in God. She believes in hope. She believes she will get through. And, she wants other single mothers to know they will, too. “No matter what you’re going through, you can get through it.”

Even in the harshest of circumstances, her love for her children keeps her going. “Every morning, I look at Conyers, and he brings me joy. Even when everything else is hard.”

A Crisis in Plain Sight

Each person I spoke with that night had different circumstances, different dreams, different pasts. But they all shared the same struggle — finding stability in a city that they feel often overlooks them. In the following section, the Rev. Patrick Burke addresses the growing demand for shelter in Wilmington and explores how we, as Christians, are called to respond.

This isn’t just a housing problem. It’s a human problem. And it’s happening in our own backyard.

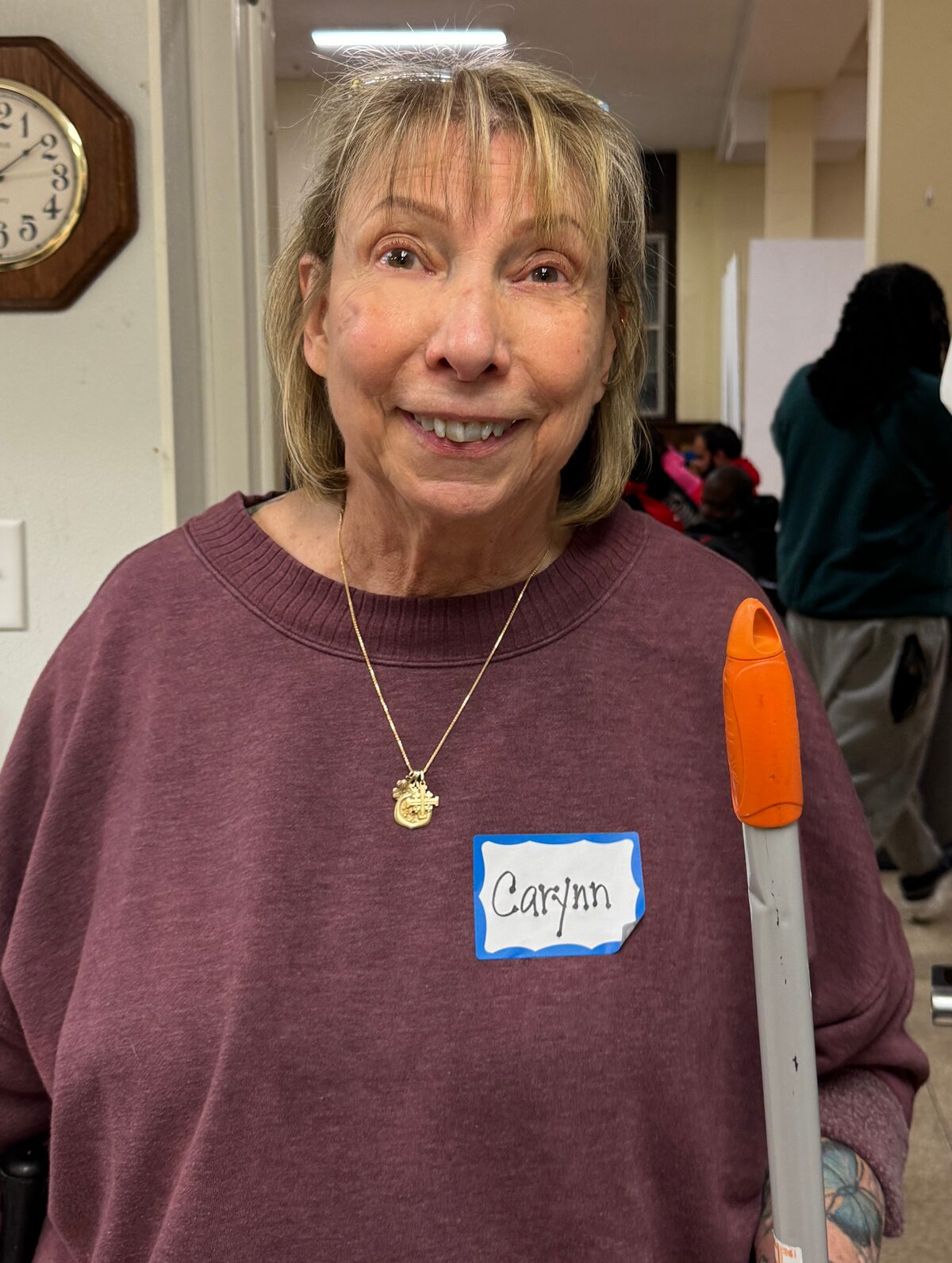

____________________________________ A heartfelt thank you to Carynn Kelley-Katz for her incredible dedication during Code Purple and for introducing me to the individuals seeking shelter one evening. Carynn’s deep care and compassion shine through in her volunteer work with the Code Purple ministry. As she shared with me, “They are like family to me, and all I want to do is show them that they matter.” Her words reflect a genuine love and respect for each person, reminding us all to look beyond the surface and truly see one another. Her offer of warm ‘good-nights’ and heartfelt hugs to each person at the end of the evening are a powerful reminder of the impact of simple, genuine love.

A heartfelt thank you to Carynn Kelley-Katz for her incredible dedication during Code Purple and for introducing me to the individuals seeking shelter one evening. Carynn’s deep care and compassion shine through in her volunteer work with the Code Purple ministry. As she shared with me, “They are like family to me, and all I want to do is show them that they matter.” Her words reflect a genuine love and respect for each person, reminding us all to look beyond the surface and truly see one another. Her offer of warm ‘good-nights’ and heartfelt hugs to each person at the end of the evening are a powerful reminder of the impact of simple, genuine love.

What Does a Faithful Response Look Like?

by the Rev. Patrick Burke

Then the king will say to those at his right hand, “Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was in prison and you visited me.” (Matthew 25: 34-37)

The Growing Need for Support in Wilmington, Increasing Demand for Shelter

How we choose to care for the most vulnerable among us says much about our community. Over the course of the last year, we have watched as the number of individuals seeking shelter and other forms of assistance around the downtown area of Wilmington has increased significantly.

during a Code Purple evening.

As one of two locations that host Code Purple in Wilmington — an emergency warming shelter when the temperature drops below 20 degrees — The Episcopal Church of Saints Andrew & Matthew (SsAM) has not only seen an increase in the number of dangerously cold days but has also hosted three times as many nights this winter as last. We have also watched the number of individuals more than double in the same time period. (Last year we averaged 30–40 individuals per night, while of late we have hosted 90 individuals per night.)

The church also provides hospitality to the unhoused community in our auditorium on Sunday mornings. That ministry has grown to support more than 50 people each Sunday. Just this past February, several newly homeless families with young children and elderly individuals found their way to the church and the Wilmington Empowerment Center (WEP), searching for shelter and support.

720 Orange Street in downtown Wilmington.

During the day, the WEP, operated by Friendship House, supports members of the community with a variety of services from hospitality to assistance with obtaining the vital records necessary to apply for jobs, housing, and other benefits. It also offers access to a computer lab, clothing, and various forms of financial assistance. In 2023 the WEP served over 3,200 individuals. In 2024 a marked increase was seen, which continues in 2025.

Beyond offering the community access to a public restroom, hospitality, and a quiet place to rest, the church often opens a daytime warming center during winter, providing refuge for more than 100 people on any given day. This response has been necessary due to more frequent severe weather and a continual decrease in the number of locations that will welcome members of the community who are unhoused.

As followers of Jesus Christ, watching more and more of our neighbors struggle to find shelter, sufficient food, and other basic necessities is distressing. As disciples, we turn to Jesus to pray for those in our community who are suffering. As Pope Francis and others have said in the past, prayer also leads us to action in the name of Christ.

How do we, as disciples of Jesus, respond to the suffering that we see in our community as this housing crisis grows? What is a faithful response to this crisis?

Many of our churches and parishioners provide direct and indirect support to those in need in a variety of impactful ways. Sometimes this means offering financial aid and volunteer support to nonprofits that serve the community, while other times, churches run their own ministries to assist society’s most vulnerable. These ministries are sacred; they are life giving; and they embody the love of Christ. They also provide a path for us to create sacred relationships built on trust and seeing the love of Christ in everyone we meet. The discussions that Cynde had with individuals embody the sense of sacred trust that flows through the work of the Holy Spirit and calls each of us to see the love of Christ in everyone we meet — especially in those who are most vulnerable.

Throughout the gospels Jesus says that he has come to bring good news to the poor. In the fourth chapter of Luke’s gospel, he reads from the scroll of the Prophet Isaiah and says, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor.” When I think about all the ways that we faithfully minister to the immediate needs of our neighbors, I think of Jesus saying this and I wonder what he means by good news. The support we provide tangibly helps those we encounter, and yet many remain within the cycle of poverty.

What if the good news includes breaking the cycle of poverty, and dismantling the systems that impoverish so many of our neighbors? One of the times that Jesus points to this is when John the Baptist, from prison, asks for signs that Jesus is the Messiah. Jesus seems to be pointing to something happening all around them — that seeing the kingdom of God breaking into the world around us is good news because things are changing for those who are oppressed by poverty.

Throughout Lent, we at SsAM will be thinking and praying about this intersection. We will discern how we might find ways to participate in dismantling the systems that impoverish our neighbors while still ministering to the immediate needs that are in front of us. We also want to invite the rest of the diocese into this discernment. Whether we are in a context with unhoused individuals living next to our churches or in a rural or suburban context where poverty seems hidden, collectively we can bear witness to the good news of Jesus working together to address the systems that impoverish our siblings in Christ in a variety of ways. But the key is that we must think and act as a collective.

How Can Churches and Individuals Provide Assistance and Support in Delaware:

There are many ways individuals and churches in Delaware can help with homelessness, from direct assistance to advocacy and community support. Here are a few:

Direct Assistance & Support

- Partner with Local Shelters & Organizations – Volunteer or donate to organizations like Friendship House, Sunday Breakfast Mission, Housing Alliance Delaware, Family Promise of Southern Delaware, and Family Promise of Northern New Castle County.

- Host a Meal Ministry – Provide hot meals, packed lunches, or pantry supplies for those in need.

- Offer Shelter Space – If possible, churches can partner with shelters to provide emergency housing during extreme weather. For Code Purple locations dial 2-1-1. Several churches in Delaware are Code Purple locations. To become a Code Purple shelter in Delaware, organizations should contact Friendship House for New Castle County, Code Purple Kent County, or Love Inc. for Sussex County.

Advocacy & Awareness

- Educate Your Congregation – Host speakers from local nonprofits to share insights on homelessness.

- Advocate for Affordable Housing – Work with local legislators and groups to support policies that increase affordable housing options.

- Join the Annual Homeless Census (PIT Count) – Participate in Delaware’s Point-in-Time Count, which helps track homelessness trends and fund solutions.

Employment & Empowerment — YWCA Delaware, Wilmington Empowerment Center, and Pathways to Employment are a few employment and empowerment centers offered in Delaware.

- Job Readiness Support – Provide resume help, interview coaching, or transportation assistance for job seekers.

- Mentorship & Fellowship – Build relationships with individuals facing homelessness through regular check-ins and social gatherings.

The Rev. Patrick Burke serves as the rector of the Episcopal Church of Saints Andrew and Matthew in Wilmington. In addition to his role as rector, Patrick is deeply involved in housing ministry and is a strong advocate for the most vulnerable in the community. Previously, he has served as a minister for justice and community collaboration in Indianapolis, where he developed innovative ministries and spiritual communities for un-churched, vulnerable, and socially marginalized young adults in urban, non-traditional spaces. rector@ssam.org

The Rev. Patrick Burke serves as the rector of the Episcopal Church of Saints Andrew and Matthew in Wilmington. In addition to his role as rector, Patrick is deeply involved in housing ministry and is a strong advocate for the most vulnerable in the community. Previously, he has served as a minister for justice and community collaboration in Indianapolis, where he developed innovative ministries and spiritual communities for un-churched, vulnerable, and socially marginalized young adults in urban, non-traditional spaces. rector@ssam.org

Cynde Bimbi is the Director of Communications and Public Relations for the Episcopal Church in Delaware. A longtime member of Episcopal Communicators, she has received numerous awards for her work in design, publications, campaigns, photography, videography, and writing. In her role, Cynde serves as the diocese’s digital and print strategist, marketing lead, graphic and web designer, social media manager, photographer, videographer, and content creator. But at the core of her work is a true passion for supporting congregations — helping parish communicators and administrators navigate challenges, develop new skills, and strengthen their outreach. cbimbi@delaware.church

Cynde Bimbi is the Director of Communications and Public Relations for the Episcopal Church in Delaware. A longtime member of Episcopal Communicators, she has received numerous awards for her work in design, publications, campaigns, photography, videography, and writing. In her role, Cynde serves as the diocese’s digital and print strategist, marketing lead, graphic and web designer, social media manager, photographer, videographer, and content creator. But at the core of her work is a true passion for supporting congregations — helping parish communicators and administrators navigate challenges, develop new skills, and strengthen their outreach. cbimbi@delaware.church

No Place to Call Home:

Voices from the Streets

and a Faithful Response

The Route of Stone and Water:

Look Up

The Gift of Invitation:

Everything Changes

Bishop's Lenten Message:

Pray More, Scroll Less

It's 'T' Time!

Churches Can't Continue...